Craft Article: "Introducing Your Next Characters: How to Outline Your Protagonist and Nemesis"

Great news! My craft article was published by Women on Writing today! Read on for some tips sure to develop your latest fictional protagonist and antagonist.

“Introducing Your Next Characters: How to Outline Your Protagonist and Nemesis”

By: Melanie Faith

Protagonists and antagonists: every story has them, or should have them. Our readers want someone to root for, someone they can identify with as they conquer problems both common and extraordinary. They also want an instigator, a character whose sole goal is to create the tension and conflict we experience in real life.

Think of these characters as paired all-stars in your novel—wherever there’s the protagonist striving to make their hopes and dreams happen with their actions, the antagonist should soon appear to work their devious deeds of mayhem to block those hopes and dreams.

Many writers delve straight into their initial scenes with their protagonist without knowing more about their protagonist than a name and perhaps an age. Certainly, many writers begin stories without knowing anything about the antagonists who will make it their purpose to mar the protagonist at every turn.

While one could free-write scenes for endless weeks or months, the more sensible approach is to do some quick but fruitful pre-writing to “meet” your protagonist and antagonist before setting your scenes to the page.

Outlining character details before writing chapters will:

* save you time figuring out what your protagonist wants,

* save you time and scenes figuring out why your protagonist is doing what (s)he is doing,

* create immediate conflict that sets your novel’s plot into motion,

* help you to pinpoint exactly why this protagonist desires what (s)he desires,

* introduce you to the antagonist’s desires and why (s)he doesn’t want the protagonist to succeed,

* and demonstrate the lengths the antagonist is willing to go to block your protagonist.

To get started, consider the following outlining exercise. Set a clock for fifteen or twenty minutes and answer these questions. Allow ideas and information to bubble up from your subconscious without editing or omitting details. Write as much or as little for each question as you wish. J

There are many, many more approaches for developing notes about your protagonist, numerous of which I’ll explore during my course Outline Your Novel with Ease, but these initial questions will get you well on your way to a juicy conflict and two well-rounded main characters.

Feel free to keep writing beyond the ding of the timer. Pick a few of these questions, or answer them all. Feel free to add details over the following hours and days as they appear to you. Keep in mind that protagonists are not all good and sweet, nor are antagonists all selfish or rude; we’re all a blend of qualities, emotions, circumstances, and missteps.

Then, after a few days, sit down to draft your initial scene. In the scene, use several details directly from this exercise.

By the way, you’ll learn more about your protagonist from this pre-writing exercise than you will include in the scene, which is perfectly normal and a great idea. Think of those “characters” you know in real life—you know a lot more about them (and they about you!) than either of you share directly when communicating.

Meet your protagonist:

* What is their childhood nickname? Do they still go by this name? Would they hide it?

* What is their birth order? Do they have siblings? Would they have liked [more] siblings or no siblings? Does anything in their background influence their thoughts about having or raising children?

* Do they live where they thought they would as a teen? Why or why not? Are they willing to move to another location? Why or why not?

* What is your protagonist’s dream job? Do they currently have that job? Do they have excuses for why they don’t have that job? If so, what are they?

* Describe a time when your protagonist was overlooked or underappreciated. What would it take to make your protagonist feel like a winner?

Meet your antagonist:

* Does your antagonist have a nickname? Do they still use it? Would they hide it?

* Has your antagonist known your protagonist since childhood? Since college? If not, when and how did your antagonist and protagonist meet?

* What was your antagonist’s initial (unspoken) impression of your protagonist? Describe their first conversation.

* What is your antagonist’s biggest regret?

* Describe a time when your antagonist felt like a winner. Then write about a time when your antagonist felt like a complete zero.

Want to learn more? Check out my 2020 classes, beginning on January 17th with Outlining Your Novel with Ease! Click here: 2020 classes info.

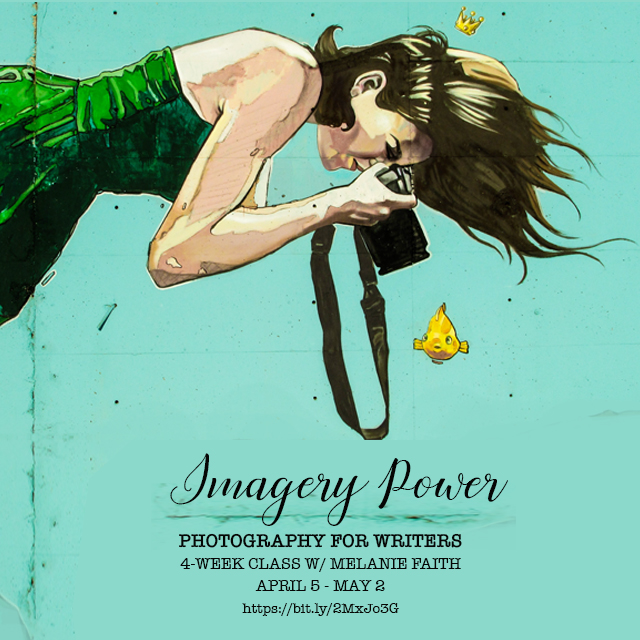

Welcome to the World, Photography for Writers!

At long last, it’s release day for my new book, Photography for Writers!

Buy your copy today at Vine Leaves Press. Signed copies also available, via my WritePathProduction Etsy Shop or via pm.

Photo by Adi Goldstein on Unsplash .

"Four Tips for Writing Fantastic Flash"

My article about flash-writing was published today. Ta-da! Give the writing exercise a spin.

“Four Tips for Writing Fantastic Flash”

by: Melanie Faith

Good things come in small packages. Chocolate truffles. Earrings. Me—okay, that last one is wishful thinking since I round my height up to 5’2”, but you get the picture.

Flash is the mighty genre that could and no exception to the small-packages rule of thumb. In both fiction and nonfiction, flash stories tell a narrative, develop a character and setting, craft conflict and tension to a surprising ending, and more—all in just 1,000 words or less. Pretty impressive!

Use these four tips and the accompanying exercise to craft some stellar flash.

· Set two characters against each other. Ever lived in a dorm? Then you know that very rarely do even two people (much less a whole group) view similar experiences the same way. Such conflict is a key component of good flash. Whether your characters compete for the same person, place, or thing or just have opposing personal, political, or ideological views, one sure way to maintain conflict within a flash is to pair two characters in a clash of goals. When I judge flash contests, one of the key disappointments is when a good flash character or concept doesn’t have enough tension to sustain the flash, so the prose falls flat.

· Ready, set, action! Your protagonist or speaker must DO something. Flashes aren’t as dynamic if the character is inert or has things done to her or him. Detail your protagonist’s physical actions and responses. Many promising flash drafts I’ve read go off the rails when they include a character reflecting on something that has occurred—which is fine for a sentence or two, maybe, but for a flash to really zing off of the page, the character must push back in deed. In real life, I need a fair amount of reflection time, but in my flash writing, I avoid it. Wind those characters up and let them move on the page! Which brings us to our next tip:

· When in doubt, include (a little) body language. Sometimes, jokingly, I’ve referred to dialogue without any speaker tags or visual imagery for several paragraphs as “floating heads,” because the characters seem to exist in outer space, without a clear physical presence. Readers don’t need to know every single cough, sneeze, or hand on the hip, but if your readers can’t imagine how characters are reacting to each other—whether through vocal tone, rolled eyes, tapping toes or shifting uncomfortably- then they probably won’t have as deep an investment in characters’ struggles. Much of what real people communicate in everyday life is demonstrated through body language; sprinkle a few well-placed images between the dialogue to show the conflict between what the character says and how the character or others physically react.

· Contradictions make better flash characters. In other words: we’re all a mess, so why not mine it? Another problem in some flash I see are characters who are one-sided, with a single personality trait that is not-so-awesome for flash: they are too agreeable. Something bad happens, and they accept it as the way things are or they make a decision to ignore it entirely. Strong writing brings us characters who have a main trait—kindness, enthusiasm, anger—and an opposing trait that rears its head now and again—selfishness, mercurial moods, humor at the wrong moment. As F. Scott Fitzgerald once said: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Guess what—we all have these two opposing sides and must function, which creates the kind of exhaustion and frustration that doesn’t always make life easy but which makes for fantastic conflict, tension, and character development in flash.

Try this exercise: Your speaker or protagonist has always reacted to injustice by ________________, but today, a different side of their personality is going to shine. Instead, they will _________________. Include inner thoughts of the character or speaker right before they decided what to do, during, and after. Include at least a line of dialogue in your flash where a person with a different opinion or view tries to stop your speaker or protagonist. What happens next? Go!

~~~~~~~~

Looking for a fun online writing class? Still a few spots in my Flash writing class that starts on Oct. 25th. :) In a Flash Details.

I’ll also be teaching a novel class in January. Outlining Your Novel with Ease Details.

"Food Writing: Introducing the Quotable Yum Factor" Article Published :)

So pleased that my article was published as a Spotlight article at Women on Writing this week. I’ll also be teaching a themed online writing class in September (scroll to the end of the post for the link to the course and more details).

“Food Writing: Introducing the Quotable Yum Factor”

By Melanie Faith

I’ve been a quote collector from way back. I can’t help but relish words of wisdom on the topic of food that demonstrate not only eating but also sharing our love for nourishment through writing is just about the best thing since, well, sliced bread.

Why food writing? you ask. Let’s take a look at three quotes that explore just why food writing sustains and entertains writers and readers:

· “First we eat, then we do everything else.” -M.F.K. Fisher

Think back to some of your first memories; most of these remembrances likely involve food, food preparation, eating, snacking, or all of the above . Do these memories involve a birthday party? There was certainly cake with decadent, butter-rich icing or the waft of cocoa powder at the first slice. What about memories of a yearly special occasion shared around the table with family and friends, like the first savory bites of Grandma’s Thanksgiving stuffing with the pecans and what was that delicious spice she always winked and called her “secret ingredient”?

Food has an undeniable connection to place, culture, and time period that can inspire evocative writing. We often recall not just what we ate and how it tasted (which is a sensory feast enough) but who we were with (or not with), the location, and other events that were occurring while we noshed.

Food brings both comfort and spark points for poetic prose and narrative verse. Try this: set a timer for fifteen minutes and make a list of foods or dishes from your growing-up and teen years and your young adult days. Any of these foods could make great material for a free write, because they are connected to wider experiences and places in your past or present. Combine setting details with food details for a richer mixture.

· “Life is uncertain. Eat dessert first.” -Ernestine Ulmer

Feel the push-pull in the above quote? That’s part of what makes it delicious, non? Tension and conflict, two hallmarks of literature, are perfect companions for writing about food as well.

As a creative-writing teacher and bookworm, I’ve read many scenes

in novels and nonfiction manuscripts where food served as a backdrop or symbolism for the deeper struggles in characters’ or speakers’ lives.

For example, you might combine a protagonist who is scared to tell his love interest something about his past with a breakfast scene in which he prepares his love’s favorite waffles. How does he avoid telling this truth, using the food as a go-between? How does he work himself up to sharing this secret? Dialogue as well as description of his actions and the food all work together to deepen the writing.

· “I have made a lot of mistakes falling in love, and regretted most of them, but never the potatoes that went with them.” -Nora Ephron

Mistakes in life and/or love, who hasn’t made some? Ephron’s quote reminds us, as writers, to employ wry humor as we look back on our pasts. It also reminds that, as disappointing or frustrating as things became, there were silver linings that sustained us.

Cooking and writing, too, share the need for a healthy sense of humor and a silver-lining attitude. Ever made a cake, following the entire recipe, but the cake fell flat or never rose at all. [Instructor raises her hand.] Ever written a draft that seemed so promising and then either stalled mid-draft or just didn’t go in a direction you expected? [Instructor’s hand again goes up.]

Food writing has two great strengths: one, there is the opportunity for humor (perhaps something unexpected, non?). I’ve read hilarious blogs and essays where a writer takes a kitchen disaster or restaurant meal gone wrong and serves up a wider truth about how we rebound and try, try again.

Also, food writing encompasses many, many genres. Its versatility is part of the reason why I love writing food scenes and, for several years now, teaching a writing workshop to encourage others to do so.

· Like poetry? Try “Figs” by D.H. Lawrence, “Ode to the Onion” by Pablo Neruda, or “After Apple-Picking” by Robert Frost.

· Enjoy personal essays and food-journal articles? How about anthologies with both? Try the annual The Best American Food Writing books for inspiration.

· How about travel writing? Yep, food writing also falls under that category, such as blogs that detail the best bistros and taco trucks in your town or city.

· I haven’t forgotten the prose writers. Many novels include scenes or even whole chapters where food plays a significant part in the narrative. The examples and sub-genres of fiction that involve food are endless, such as: classics like the party scene in Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby to children’s books like Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, YA like Stephanie Burgis’ The Dragon with a Chocolate Heart, Contemporary Fiction like Kirstin Chen’s Soy Sauce for Beginners, Romance like Yolanda Wallace’s Month of Sundays, Historical Fiction like Crystal King’s Feast of Sorrow: A Novel of Ancient Rome and Philip Kazan’s Appetite, and many more.

Go ahead: do a little “food-writing research” today. Pick one of the above food-writing genre examples and research and/or read the piece(s). Then, give food-writing a go on your own. Whether in poetry, prose, or a combination of both, your writing is sure to be richly filling and enhanced with eating imagery.

I’ll be teaching an online writing class, beginning Friday, September 13th. Just four more openings left. Click for more details about this delicious course. Food Writing for Fun and Profit.

My MFA-Themed Article Published Today

Ever wonder when to apply for the MFA? Wonder about my before-MFA journey?

Excellent news: my article, “When’s the Right Time to Pursue an MFA?” was published this morning at NUNUM. Ta-da! :)

Photo: part of my Artifact Series. :)

My Lyric-Poetry Article Published :)

So excited to announce that my article, “Three Types of Lyric Poetry to Fire up Your Writing Practice,” was just published. Click on the name of the article above to read it.

"Six Insider Tips for Poetry-Publication Success"

My article was published today at Women on Writing! Enjoy. :)

“Six Insider Tips for Poetry-Publication Success”

By: Melanie Faith

Photo courtesy of: Trust “Tru” Katsande, @iamtru, unsplash.com

So you’ve been writing poems for months or years, and you’ve decided that you’d like to try for publication. Great idea!

You’re probably wondering where to begin and how to know which poems to submit. Here are some insider tips to encourage your poetry-submission process and to make it easier.

1. Put your best poem forward. Open your submission packet with your strongest poem. Make sure to edit that poem so that its first lines/stanza includes no warm-up or filler words. Grab the reader’s attention with an intriguing image or beautiful, meaningful language from the get-go.

2. Follow posted guidelines, to a t. Always check online guidelines (the vast majority of literary magazines have them posted, whether at Submittable or their personal webpage).

Many journals request three to five poems at a time, but there are some exceptions to that rule. Don’t send more poems than the maximum number listed; it would be a shame for your submission to be automatically rejected for not following instructions (I admit it’s happened to me more than once).

Guidelines will also include the specific genres requested (some journals only read prose, for instance, or they only read one specific genre per issue).

3. If in doubt—ask! What if you’ve written a prose poem, but that’s not listed in the guidelines? Or what if the submission guidelines don’t include a specific number of poems to submit? What if you’re wondering about simultaneous submissions? These are three excellent reasons to send a quick email to editors; I’ve certainly done so for these reasons and others.

Politely introduce yourself and list that you are a poet, ask your question, thank the editor(s) for their time, and include your email address and/or other contact information. Easy-breezy.

Do remember to respect their time: only contact them once; wait for an answer. Even a month isn’t too long to wait (remember that they often have hundreds of submissions per issue and busy lives outside of their jobs). Usually, though, you’ll hear back from editors within a few days or much less.

I’ve found editors quite generous with their time (many are also writers) and very willing to clarify or consider various types and themes of poetry even if they haven’t listed them directly in the guidelines. Just make sure, as a courtesy, to double-check and to send the query email before sending the work; never just assume you can send whatever you want.

4. Consider the poetry-publication process to be more of a marathon than a sprint. Adjust your (speed) expectations just a bit. Yes, I know— I’m also very used to the instant gratification of the internet. On the other hand, the pace of creating, editing, and submitting new poems is a slower, yet no less meaningful, art.

Set monthly goals for yourself (mine is to submit at least three submissions of poetry, photography, or prose per month, year-in-year-out), and then give yourself room to continue exploring your genre. Publication might not happen overnight (it’s not fast food or on-demand content), but it will happen. Keep submitting.

5. We’re living in an exciting time, where we can self-publish some or all of our content. You may feel free to share, from time to time, on your blog (or to guest blog) or on social media posts, but keep in mind that many online and print publications consider work published online anywhere as already published, and so it may knock that poem out of the running for submitting to literary magazines in the future. For 100% self-publishing poets that might not make any difference. For other poets, a more balanced approach might be of interest.

I’ve known writers who shared sneak-peaks of their poems or poetry-in-progress online to engage with readers, but they kept other poems for literary-magazine submissions, which is one great strategy for developing an audience while also pursuing publication. As you go, you’ll find a combination of withholding and sharing that works for you.

6. Continue to write and to develop your skills while waiting to hear back from editors and publishers. I started to submit work regularly around the time I graduated from college. I didn’t have the money to go to graduate school for my MFA right away, so for a few years I started my teaching career and kept writing in my free time while I also took a few other positive steps to continue to learn and to grow as a poet. I participated in open mikes and readings. I joined a writing group for a few months to meet others who were also on this poetry-penning path. I workshopped, both within a larger group and one-on-one with a new writing friend. I met some new writing pals online and we shared our work through emails. By the time, six years later, I had paid off my college loans and was able to apply to grad-school programs, I had steadily built my writing skills and had publication credits from several literary magazines.

Never underestimate the power of networking for growth as a poet. Join a poetry writing/reading group or start one in your community or online.

Take a noncredit poetry-writing class, again in your community or online at WOW!

Swap drafts with a poetry buddy once a month, to offer each other encouragement and helpful suggestions.

Read poetry journals and books online and in print to become aware of the markets for poetry as well as the work of your fellow poets.

Any or all of these suggestions will prove a great asset to your poetry-writing and -submitting processes.

Care to learn more? Consider my May class, Poetry for Publication: an Insider’s View. Here’s the scoop and skinny:

Get Your Poetry Published!

Poetry for Publication: An Insider’s View by Melanie Faith

START DATE: Friday, May 3, 2019

END DATE: Thursday, May 30, 2019

DURATION: 4 weeks

COURSE DESCRIPTION: Ever wonder how to go from scratching drafts in a notebook to sending poems to literary magazines that will get chosen for publication? Ever pondered what editors look for in literary journal submissions? How should we keep track of poetry submissions, and should we do that odd thing: “simultaneously submit?” Ever started a manuscript only to find it all a bit daunting to know what poems to include and which to omit? Want to prepare a chapbook or full-length collection but not sure where to start? How do we get past stalled drafts or stalled manuscripts to persevere and find our writing and reading community? If you've wondered any of these questions, then this is your workshop! Learn real-world, first-hand advice and tips from a poet who has judged poetry contests, published chapbooks and a full-length collection, and regularly submits poetry to literary magazines. Just because it’s chockfull of practical information, doesn’t mean it won’t be fun.

In this four-week workshop, we’ll explore what literary magazines look for in submissions, how the instructor as well as several other poets put together chapbooks and/or larger collections of poems, and insider advice for editing work with an eye towards publication. Students will read Ordering the Storm: How to Put Together a Book of Poems edited by Susan Grimm as well as excerpts from Poetry Power by Melanie Faith. There will be a private group for students to discuss the literary life, ask specific questions related to putting together a submission and/or manuscript, and for sharing of literary resources, such as markets and quotations about the poetry writing and submission process.

Topics covered will include: Best Foot Forward: Arranging a Poetry Manuscript; Journey without a Map; Finding, Unifying, and Revising the Body of Our Work; Throwing Poems at an Editor to See If They Stick; Keeping Company: Thoughts on Arranging Poems; Write Opportunity, Wrong Timing; Wild Cards: 8 Tips for Choosing Poems for Submission; The Art of Offering Feedback; The Plandid and Other Splendid Editing Options; Lavender Disappointment: on Adjustment of Expectation and Stalled Drafts; 76 Rabbits out of a Hat: or: The Quirky Tale of How One Poem became a Whole Book; 21-Century Publishing & Guidelines for Finding Your Ideal Audience; Spring out of a Writing Rut! 8 Tips for Getting back to Business, and more.

"Break Out Your Cameras to Enhance Your Image Writing" by Yours Truly

My craft article appeared today at Women on Writing. Ta-da! :)

Photo by Vera Ja, https://unsplash.com

“Break Out Your Cameras to Enhance Your Image Writing”

By Melanie Faith

For a year, off and on, I shot a series of photos called "In the Green." The series included many different subjects, some that you might expect (from an emerald, leafy landscape to the green whirls of a decorative cabbage I saw at a farmer’s market), and others that might surprise. A perfect example of the latter was the mint-hued upright piano I spotted at a craft store in the Midwest while visiting my sister one summer. Needless to say, I couldn’t let that piano, which also sported a giant ivory stencil of a splash of roses above the keyboard, go undocumented.

Not all of the elements in each shot were green—such as three clover-shaped skeleton keys I couldn’t resist from an auction—but I incorporated a Kelly green into the background.

Each image, several of which have been published over the past year, including in Fourth & Sycamore, includes at least one aspect of the color I’d chosen, which also happens to be my personal favorite. (A little trivia for you.)

My photography practice has enhanced my writing practice for years, and vice-versa. What can photography bring to enhance our writing skills on the page and screen?

- Photography is imagery-focused, just like writing. Do you like to take photos of your family dog or cat? How about landscapes? Or food shots from restaurants or your own kitchen? What about your children or grandchildren? Or sports? In each of these types of shots, and more, there is a subject in your composition that you zero in on, to the exclusion of other details in the shot. The same is true for our writing. In our writing practice, we narrow down the subject we’d like to explore and the best genre to explore it (poetry, nonfiction, fiction, and flash, to name a few options).

Just as in our compositions we decide if we want to take a long, wide view (as in a landscape) or the close-up view (as in a macro or micro shot), in our writing, we make choices about how we will present the protagonist(s) or antagonist(s). What will be their main motivations? What action will be the catalyst for beginning the story in conflict, in media rest? What word pictures will bring to life the tone and theme in our poem?

- Photography evokes numerous senses within visual imagery, just as good writing does. No, we don’t have scratch-and-sniff photos yet, but a great photo of a box of popcorn triggers our memories and associations with the scents and textures of popcorn just as multi-sensory imagery in prose or poetry within the minds of readers.

- Photography teaches us about connections, symbolism, and resonance. Just like in our writing, in photography there’s the surface subject—perhaps a platter of enchiladas—and then there’s the deeper meaning of the picture—your grandfather taught you to include a lime wedge to garnish them and so you always make yours with limes at the ready. The evocative personal and background details in such a shot will influence not only why you chose to document your delicious dish, but also will affect the way that viewers approach and appreciate the composition, even if they don’t know 100% (or any) of the backstory. Good photos, just like good writing, reveal key, carefully-selected details that draw in the audience.

- Photography, much like writing, is self-expressive and just plain fun. It can be easy, amidst craft talk, to forget that there’s a magical and exciting sense of exploration in both art forms. Many times, I’m surprised and entertained by the subjects and themes that both my lens and pen create and how much they share in common.

Try This Prompt! Choose a color from the ROY G BIV spectrum (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). Make a photo every day for four or five days of something with this color. Warning: it’ll only take a day or two until you notice the color everywhere.

Feel free to use the camera on your phone, if that’s easier than hauling around a larger camera.

On the last day, use one of the images from your photos as a prompt to kick-start a new poem, short story, scene, or essay. Include unique descriptions to denote each color in your writing. Thesaurus.com is a wonderful resource for hue synonyms.

Consider continuing to take photos in your series for as many days or weeks as the idea appeals, and then repeat this exercise as often as you’d like with a piece of writing inspired by your new photo compositions.

Need more inspiration? Consider my upcoming Imagery Power: Photography for Writers class.

"Three Reasons Why Flash is the Genre for You"

My spotlight article was published today at Women on Writing. Enjoy!

“Three Reasons Why Flash is the Genre for You”

By: Melanie Faith

Don’t let the small size of flash fiction and nonfiction fool you—there’s a ton to recommend this little-genre-that-could.

· Got sci-fi? Got a personal essay? Got romance? Got magical realism? Great! Flash is diverse in subject matter. Just like its longer contemporaries, flash is a hot genre sought by many markets. I’ve seen seeking-submission ads just this week for flash fiction in anthologies, magazines, and for conferences. One market sought speculative fiction, which includes science fiction, fantasy, magical realism, and slipstream subgenres. Another market asked for flash memoirs, romance, horror, adventure, and cowboy tales. Still another market seeks environmental and travel narratives in flash. I’ve seen (and submitted my own flashes to) markets for humorous flash as well.

Both fiction and nonfiction flashes are prized by editors, so whether you like to write about yourself or to create characters, there’s room in flash for either. Or why not try writing flash in both genres? In my craft book, In a Flash! Writing & Publishing Dynamic Flash Prose , I offer oodles of practical tips and prompts for exploring and marketing flash in fiction and nonfiction.

Clearly, just about any topic you could spend a novel, novella, (auto)biography, or short story writing about can translate well as a subject for flash, too.

· Another advantage of flash is that most markets want multiple flashes at once. This is great news, because if they want three or five stories at a time, then you have three or five chances to wow them. Include what you think is your strongest flash first in the submission packet. Not sure which is your strongest piece? Ask a friend which piece stands out to them.

· Worried about not having enough plot development within such a small space? No worries. Many of us writers are already used to writing texts and Tweets. Trying our hands at flash in its many styles should be a snap.

Flash is economical but also has wiggle room to fit any plot. While the top word-count for flash is often set at either under 1,000 words or 750 words, that’s not the only length markets seek for flashes they publish.

Ever head of the “drabble?” That’s a flash of exactly 100 words. There’s an excellent book by Michael A. Kechula, called Micro Fiction: Writing 100 Word Stories (Drabbles) for Magazines and Contests , that details more about how to write and submit these 100-word gems.

There are also fifty-word stories, two-sentence stories, and even six-word stories (you read that right). I’ve seen contests and literary magazines, like Narrative Magazine , that seek six-word stories and often pay for them.

Whatever subject, style, or word-count works for you, there’s sure to be a market eagerly awaiting your flash submission!

~~~

Want to learn more?

Check out my upcoming online workshop that begins on Friday, March 15th. Here’s the scoop and the skinny:

In a Flash class

Signed copies of my book for writers that is chockfull of great tips and examples for nonfiction and fiction flash writers, In a Flash: Writing & Publishing Dynamic Flash Prose, available at WritePathProductions.

A sale book bundle, of both my flash- and poetry-writing books, is also available for book lovers at Etsy.